Intuitive Interaction from a User Experience Perspective

People all agree that products should be intuitive to use – but what does this include? What do users experience when they talk about intuitive interaction?

The INTUI Model wants to address these questions and explores the phenomenon of intuitive interaction from a User Experience (UX) perspective. It combines insights from psychological research on intuitive decision making and user research in HCI as well as insights from interview studies into subjective feelings related to intuitive interaction. This phenomenological approach acknowledges the multi-dimensional nature of the concept and also reveals important influencing factors and starting points for design.

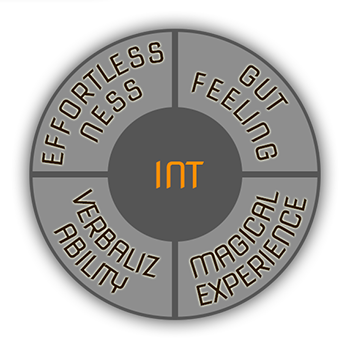

INTUI Model

The INTUI-model suggests four components of intuitive interaction, namely, Gut Feeling (G), Verbalizability (V), Effortlessness (E) and Magical Experience (X).

The components’ relative specifications build different types of intuitive interaction, so-called INTUI-pattern. The four components can be assessed by the INTUI-questionnaire. A number of empirical studies explored the components’ relative specification with regard to first level (product, user, context) and intermediating, second level influencing factors (usage mode, judgment integration, domain transfer distance).

.png)

Components

-

Gut Feeling

Intuitive interaction is typically experienced as being guided by feelings. It is an unconscious, non-analytical process. This widely parallels what we know from research in psychology about intuitive decision making in general. For example, Hammond (1993) describes intuition as a "cognitive process that somehow produces an answer, solution, or idea without the use of a conscious, logically defensible step-by-step process." In consequence, the result of this process, i.e., the insight gained through intuition is difficult to explain and cannot be justified by articulating logical steps behind the judgment process. Despite the complex mental processes underlying intuitive decisions, the decision maker is not aware of this complexity, and the process of decision making is perceived as rather vague, uncontrolled and guided by feelings rather than reason. Intuition is simply perceived as a "gut feeling". This also became visible in our user studies and peoples’ reports on intuitive interaction with different kinds of products. Many participants based their judgment on a product’s intuitiveness on the fact that they used it without conscious thinking and just followed what felt right.

-

Verbalizability

Users may not be able to verbalize the single decisions and operating steps within intuitive interaction. Researchers in the field of intuitive decision making discussed different mechanisms that could also be relevant for users' decisions while interacting with technology. For example, Wickens and colleagues (1998) argue that this is because intuitive decisions are based on stored memory associations rather than reasoning per se. Another factor is implicit learning. Gigerenzer (2013) argues that especially persons with high experience in a specific subject make the best decisions but, nevertheless, are the most incapable when it is about explaining their decisions. They apply a rule but are unaware of the rule they follow. This is because the rule was never learnt explicitly but relies on implicit learning and this missing insight into the process of knowledge acquisition implies that it is hardly memorable or verbalizable. The aspect of decision making without explicit information also becomes visible in the position by Westcott (1968), stating that „intuition can be said to occur when an individual reaches a conclusion on the basis of less explicit information that is ordinarily required to reach that conclusion.” Similarly, Vaughan (1979) describes the phenomenon of intuition as “knowing without being able to explain how we know”. Klein (1998) rather sees the reasons for missing verbalizability of intuitive decisions in the nature of human decision making per se. He claims that people in general have difficulties with observing themselves and their inner processes and, thus, obviously have troubles with explaining the basis of their judgments and decisions.

-

Effortlessness

Intuitive interaction typically appears as quick and effortless. In our studies, many users emphasized that they handled the product without any strains. Before starting conscious thinking, they had already their goal .This is also mirrored in the descriptions of intuitive decision making in psychology. For example, Hogarth [26] claims that “The essence of intuition or intuitive responses is that they are reached with little apparent effort, and typically without conscious awareness.” In general, intuition produce quick answers and tendencies of action, it allows for the extraction of relevant information without making use of slower, analytical processes. On a neuronal basis, the quick decision process may be explained by the much quicker processing of unconscious processing (Baars, 1988; Clark et al., 1997).

-

Magical Experience

Intuitive interaction is often experienced as magical. In our studies in the field of interactive products, this was reflected by enthusiastic reactions where users emphasized that the interaction was something "special", "extraordinary", "stunning", "amazing", "absolutely surprising" - or even "magical". Research in the field of intuitive decision making reveals a number of mechanisms that may add to this impression. First of all, most people are not aware of the cognitive processes and their prior knowledge underlying intuition, so that intuition appears to be a supernatural gift (Cappon, 1994). They are not aware that they acquired that knowledge by themselves rather than receiving it by magic or revelation. And even if one knows about intuitive processing and the role of prior knowledge, it is still not directly perceivable. As Klein (1998) argues, the access to previously stored memories usually does not activate single, specific elements but rather refers to sets of similar elements. This aggregated form of knowledge makes one’s own contribution to intuition hard to grasp, and people possibly become not aware of the actual source of their intuition. In the field of interactive products, the experience of magical interaction may further be supported by introducing a new technology or interaction concept, so far not applied in this product domain (e.g., introducing the scroll wheel in the domain of mp3 players).

First-Level Factors

-

Product

Of course, a central influencing factor for the experience of intuitive interaction is the product itself. Small differences in the interaction concept can evoke significant differences in the overall evaluation and judgments on intuitiveness. For example, in one of our first studies we contrasted two mp3 players (see Ullrich & Diefenbach, 2010). Due to slight differences in the operational controls player A was rated as more intuitive than player B. With player A, the upper side of a button (marked with a "+") had to be pressed to raise the volume, and the lower side (marked with a "-") to reduce it. With player B, the function of the upper and the lower part of the button was reversed.

-

User

Also characteristics of user and the particular context of use must be considered to understand the emerging experience of intuitive interaction. As already argued by others (Mohs et al., 2006), intuitiveness is not a product feature but depends on the interplay between system and user in a given context. One of the most relevant user characteristic for intuitive interaction is the user's prior knowledge. First of all, the transfer of relevant prior knowledge to the current use situation is a prerequisite for intuitive interaction to occur...

-

Context

... Moreover, the degree of prior knowledge in a given product domain affects the specific type of resulting experience and different INTUI components become more or less relevant for the global judgment of intuitiveness. In several studies we showed that for novice users Magical Experience is most relevant whereas for expert users judgments on intuitiveness rather depend on Effortlessness (see Ullrich & Diefenbach, 2010).

Second-Level Factors

-

Usage Mode

Also the usage mode affects the specific experience of intuitive interaction. In a goal-related usage mode, focused on the achievement of single specific tasks (e.g., booking a train ticket, doing a data backup), users may feel a stronger need for reflection and control than in explorative usage modes, which in turn provide more room for experiential needs. Even in the interaction with the same product (e.g., mobile phone) we found a varying relevance of the INTUI components depending on the task/usage mode: For example, the relevance of the Verbalizability component in goal than in action modes (Ullrich & Diefenbach, 2011).

-

Domain Transfer Distance

Finally, the experience of intuitive interaction and the resulting INTUI pattern depend on the domain transfer distance, i.e., the relation between the application domain and the origin of prior knowledge relevant for intuitive interaction. We integrated these assumptions in our model of domain transfer distance (Ullrich & Diefenbach, 2011). In a recent study, we tested these in an empirical study which widely confirmed our so far only theoretical model. While Effortlessness and Verbalizability were more characteristic for use cases with low transfer distance, Gut Feeling and Magical Experience were more characteristic for use cases with high transfer distance. Moreover, use cases with high transfer distance were perceived as more appropriate representatives of intuitive interaction (read more in our upcoming publication).

-

Judgment Formation

Interaction proceeds along time, consisting of many single steps and impressions of more or less intuitive interaction, which are then integrated into an overall judgment on the product's intuitiveness. In a previous study on photo editing software, single “non-intuitive” functions led to a significant downgrading of the products' overall intuitiveness (Ullrich & Diefenbach, 2011). To establish an impression of intuitive interaction, it needs a consistent impression of getting along with the product, whereby one’s own subjective impression of being effective was found to be even more important than objective task performance (e.g., level of task completion, time of task completion). However, this confidence in the product and one’s own ability to handle it could also be diminished if the flow of intuitive interaction is destroyed by sub-optimal solutions for single functions. For producers, this finding highlights the risk of cluttering a product with too many functions which may not be consistent with the rest and, therefore, imply a tradeoff in terms of perceived intuitiveness